Simon Smyth 🎥 41 years ago today as I write this, the Sabra and Shatila massacre of men, women and children started in the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon.

Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel was killed sparking a massacre of thousands of Palestinian refugees by his Christian Phalangist followers. The Israelis wanted him to rule the fractured country so they were angry too.

A phone call is made to the Israeli Defence Minister Arik Sharon to warn him of the massacre, "Thank you for bringing it to my attention. Happy New Year," Sharon said before going back to sleep.

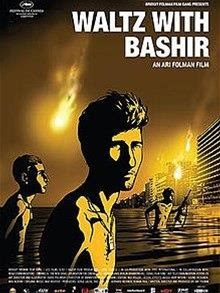

It is an animation style film. The film tells the story of a film maker (the director himself) speaking to a number of his old friends from the Israeli army. He is trying to piece together what happened during the War in Lebanon as he has no memory of it. This docudrama feels palpably real and is as close to his truth as we will get. The interviews, stories and the speakers themselves are real except for two participants whose appearance and voices are disguised.

I would recommend this film despite it being a heavy watch as I believe it is valuable education wise and is an excellent story. Despite or because of the horror there is much to be learned. Stories like this should spur efforts to halt the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and elsewhere.

I note how the film made two direct comparisons with Nazis and the Warsaw Ghetto. I would never make these comparisons myself, believing the ethnic cleansing of Palestine can stand on its own. The genocide of the Second World War and that of the Armenians in Turkey or the Belgian Congo are all different. I note it purely because the comparisons in this 2008 film would be censored or shouted down today.

Despite watching this film before and being fully aware that live footage was coming at the end, I was unprepared and couldn't stop crying.

There are many good films about the Palestinian plight and this one deserves our attention particularly if you shy away from an Israeli soldier's perspective.

It lasted 3 days. I have watched this Israeli made film 4 or 5 times before. A powerful anti-war film bordering on traumatic.

Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel was killed sparking a massacre of thousands of Palestinian refugees by his Christian Phalangist followers. The Israelis wanted him to rule the fractured country so they were angry too.

A phone call is made to the Israeli Defence Minister Arik Sharon to warn him of the massacre, "Thank you for bringing it to my attention. Happy New Year," Sharon said before going back to sleep.

It is an animation style film. The film tells the story of a film maker (the director himself) speaking to a number of his old friends from the Israeli army. He is trying to piece together what happened during the War in Lebanon as he has no memory of it. This docudrama feels palpably real and is as close to his truth as we will get. The interviews, stories and the speakers themselves are real except for two participants whose appearance and voices are disguised.

I would recommend this film despite it being a heavy watch as I believe it is valuable education wise and is an excellent story. Despite or because of the horror there is much to be learned. Stories like this should spur efforts to halt the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and elsewhere.

I note how the film made two direct comparisons with Nazis and the Warsaw Ghetto. I would never make these comparisons myself, believing the ethnic cleansing of Palestine can stand on its own. The genocide of the Second World War and that of the Armenians in Turkey or the Belgian Congo are all different. I note it purely because the comparisons in this 2008 film would be censored or shouted down today.

Despite watching this film before and being fully aware that live footage was coming at the end, I was unprepared and couldn't stop crying.

There are many good films about the Palestinian plight and this one deserves our attention particularly if you shy away from an Israeli soldier's perspective.

⏩ Simon Smyth is an avid reader and collector of books.