John Crawley ✍ delivered the address at a commemoration in Dublin on 26-August-2023 for those twelve republicans who lost their lives on hunger strike in British prisons.

Forty-two years ago today, the hunger strikes in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh were still in progress. Ten Irish Republican prisoners had died of starvation, and ten more were refusing food. The last to die, INLA Volunteer Mickey Devine, passed away on August 20th. The hunger strikes would be called off on October 3rd. Many in the crowd today had not yet been born; for them, it is a historical event. Others of us were young men and women in 1981 and remember it as a contemporary event. To Republicans of all ages, that fateful period is seared into our souls as a defining moment in Irish history.

A sacrifice of such magnitude, suffering, and selfless devotion inspires admiration in even the most cynical of those motivated primarily by material self-interest. People who wouldn’t dream of skipping breakfast for any cause or principle couldn’t help but feel a measure of respect for the hunger strikers’ inspirational sacrifice. It also encouraged those of a more opportunistic mindset to see in the hunger strikes a moral well to draw from - an event to be relentlessly plundered to augment the electoral capital essential to advancing their private political ambitions.

The issue of political legitimacy has been at the core of much of what Irish political hunger strikes have been about, whether Irishmen and women have the fundamental right, as stated in the 1916 Proclamation, to organise and train her manhood to assert in arms the independence and sovereignty of Ireland, an Ireland defined by the Proclamation as the whole nation and all of its parts. Or whether this activity can be viewed by the enemies of Irish freedom as criminal acts.

Usually, when Irish Republican hunger strikers make demands, they are not presented in such stark ideological terms. But few who have been in prison can doubt that the sacrifices made and the hardships endured during protests were not about obtaining for others an easy life in jail but a real defence of our legitimate right to fight for the full freedom of our country without being treated as common criminals.

Great play is made of the narrative that the hunger strikes of 1981 paved the way for electoral politics for the Provisional movement back when it could still claim to be a Republican movement. Long before former comrades began advocating for a two-nations ‘New’ Ireland instead of the one-nation Republic we were assured they would lead us to. This narrative has become so embedded and unchallenged that it has evolved in some circles into the delusional claim that the hunger strikers died for the Good Friday Agreement.

Why does Britain continue to interfere in our internal affairs and strive to constitutionally enshrine and manipulate our differences and divisions? First and foremost is the strategic imperative of maintaining the political and territorial integrity of the United Kingdom. Modifying Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution from a territorial claim to a notional aspiration was a significant victory for the British. The Brits and the Unionists had continually protested that these articles were the real impediments to peace and stability, not partition. Articles 2 and 3 attempted to address the injustice of partition by declaring that Ireland is one nation. It had been treated as one nation by England for hundreds of years. Weakening Dublin’s claim to the six northeastern counties gives a veneer of democratic legitimacy to partition. It demonstrates that the Irish government has partnered with London in declining to acknowledge Ireland as one democratic unit and has conceded that fact in an international agreement. It is a credit to the negotiating skills of the British that diluting the Irish territorial claim to Ireland as a whole was the only binding constitutional change required by the Good Friday Agreement.

The British never forget that Ireland is their back door. England’s initial reason for invading Ireland was to enrich themselves through land and taxation and to prevent other European powers or contenders for the English throne from using Ireland as a base of operations. When British intelligence and security analysts cast their gaze across the Irish Sea, they observe an island of over thirty-two thousand square miles covering vital approaches to Britain’s national territory and seas. A land mass that permits rapid access to areas of the North Atlantic crucial to British defence interests, particularly the naval choke point between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom that Russian ships and submarines must navigate to reach the North Atlantic. An island whose territorial waters contain, or are in close proximity to, three-quarters of all underwater fibre-optic cables in the northern hemisphere. Cables that carry approximately ninety-seven percent of all global communications. Another consideration is that Britain’s strategic nuclear deterrent, consisting of Trident ballistic missiles on Vanguard-class submarines, is based at Faslane in Scotland. These subs have to pass through the narrow North Channel between Scotland and the North of Ireland when leaving or returning to base. Under no circumstances would a government independent of the United Kingdom be allowed unfettered control of that channel’s western flank if it can be avoided.

The Brits see in Ireland a bread basket and cattle ranch. An unsinkable aircraft carrier and potential ports for their warships and submarines. An island with approximately two million men and women of military age. An island where six of its counties are members of NATO, and the remaining twenty-six must somehow be manipulated or conned into joining.

The Brits see what they have always seen in Ireland. A geographical, material, and human resource to be exploited and one that must never be encouraged to become a united, sovereign, and independent Republic that could conceivably develop policies for the benefit of the Irish people that conflict with Britian’s strategic interests.

A crucial component of British strategy is reshaping the narrative on Irish unity. Wolfe Tone’s belief that unity between Planter and Gael would be achieved through breaking the connection with England and forging a joint civic identity is best replaced by, among other things, the concept of unity through commemorating joint service in the First World War when Irish Catholics and Protestants engaged in the mutual enterprise of killing Germans in Flanders. Some Nationalists believe that relationships with Unionists can be enhanced through attendance at British war commemorations and sentimentalising joint military service in the Imperial Army that executed the 1916 leadership - emphasising at all times that the only unity that matters lies in our cross-community debasement as levies and mercenaries for the foreign country that conquered us. As part of this campaign, British war memorials are springing up all over Ireland, and elements of the Irish Defence Forces play an increasing role as a ceremonial wing for the British army. Many of those pushing this agenda support entering NATO in the belief that Irish national security can best be preserved by joining in a military alliance with the country that endeavoured most to subdue us and continues to claim a substantial portion of our national territory.

Anyone who believes the British government will simply leave Ireland when the unionist population dwindles to an unsustainable level and close the door behind them is mistaken. The Brits play the long game and are working now, as they have been working for years, to shape the strategic environment and set the conditions for the constitutional future of a united Ireland that will work to their benefit. London can live with a united Ireland within the British Commonwealth and NATO. It will not tolerate a sovereign Republic immune to its influence. At the heart of the so-called Irish peace process lies the hidden agenda of a British war process.

Unionists did not partition Ireland - England did. It did so for deeper and far more strategic reasons than the refusal of a minority in six Irish counties to become subject to the democratic will of a national majority. England did not claim jurisdiction in Ireland for the benefit of unionists. England’s conquest of Ireland began centuries before the plantations. There was no Union and no Unionists when England’s sword first cut its genocidal swathe through Ireland. It doesn’t care about unionists beyond their utility as a bulwark against the evolution of a national civic identity. Ulster Unionists are pro-British for deep historical reasons that cannot be glibly dismissed, but they are not the British presence and must not be made so. The British presence is the presence of Britain’s jurisdictional claim to Ireland and the civil and military apparatus that gives that effect.

A relentless campaign is being waged to condition the Irish people to accept and legitimise a British constitutional component as an essential ingredient of a united Ireland. Unionists may be the excuse for this, but they are not the reason. The British will retain enormous influence in the internal affairs of this country if given a constitutional mandate to represent citizens from the Ulster Unionist tradition in the ludicrously named ‘New’ Ireland. The Brits will form alliances and build the political prestige of the leadership of any community who will help them pacify, normalise and stabilise the status quo. Britain may not always be able to rule Ireland directly, but with the help of an enduring civic division, it can help prevent us from harmoniously ruling ourselves.

When those who endorse the Good Friday Agreement speak of re-imaging a ‘New’ Ireland, what they really mean is refashioning the division between Planter and Gael and giving it a truly national dimension. When they speak of creating a United Ireland for everyone, they mean making all of Ireland British enough to encourage unionists to feel comfortable in it. Suggestions include discarding the national flag, changing the national anthem, and the South of Ireland re-joining the British Commonwealth. They talk of a New Ireland, an Agreed Ireland, a Shared Island. What they never speak of is the Irish Republic.

For a Republican, reaching out to unionists does not mean reaching out to them as foreigners who happen to live here but as our fellow citizens. Foreigners are born in another country. The vast majority of Ulster Unionists were born in Ireland. They must not be treated as the civil garrison of an alien state. That is not pluralism; that is submitting to the social and political modelling of colonial conquest. Robert Emmet did not request his epitaph be withheld until his country had taken its place as two nations among the nations of the earth.

Britain has no natural affinity with Orangeism beyond one of utility. The Brits had never demurred from negotiating over the heads of their allies in Ireland when it suited their interests. Tony Blair was quite happy to dismantle the Orange state if, by doing so, Westminster’s regional assembly at Stormont could achieve nationalist buy-in and become politically viable. Of course, Unionists didn’t like that. Many are motivated by an intense anti-Catholicism few Englishmen share. But the Provo trope of equating Unionist unease with impending nationalist victory is base sectarian reductionism.

Why is New Sinn Féin so heavily invested in Pax Britannica? Why have they internalised Britain’s definition of peace even though it was the British who injected the sectarian dynamic into Irish politics and are primarily responsible for political violence here? How have they been co-opted into a concept of Irish unity that converges with Britain’s analysis of the nature of the conflict and Britain’s strategy to resolve it?

There are many reasons for this Damascene conversion, but a key one is based on a similar principle that Free Staters followed after signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty - if you cannot do what counts, you make what you can do count. To do what counted to achieve the Irish Republic proved too dangerous and daunting for many Staters, so they decided to make the Treaty count, save their skins, open lucrative career paths, and shift the goalposts from the 32-county Sovereign Republic to a 26-county Dominion of the British Empire subordinate to the King. They then told their supporters that achieving managerial control of a state was what they had been fighting for all along and, thus, had won the war.

The Free State then proceeded to create a myth of ‘our’ Irish democracy defending itself against the ‘purists’ of Irish republicanism. The thing about democracy in Ireland is that the British have had centuries to mould it in their interests. They began, in part, by founding Maynooth Seminary in 1795. A major purpose, besides preventing the Irish Catholic clergy from being tainted by democratic and republican ideals acquired from a continental education, was to train the priests and bishops who would educate a rising Catholic middle class from whose ranks would emerge a loyal nationalist leadership amenable to reconciling Irish nationalist aspirations with British sovereignty.

The degree to which Britain succeeded in nurturing a loyal nationalist leadership can be seen in the Irish Parliamentary Party’s policy of harnessing Ireland to England’s war chariot in 1914 and John Redmond’s description of the 1916 rising as treason against the Irish people.

For republicans, democracy means popular control over public affairs by a free, informed, and equal citizenship without external impediment. For the British, democracy in Ireland is any mechanistic exhibition of electoral theatre that achieves a desired result despite the use or threat of force, bribery, censorship, partition, gerrymandering, or sectarian interventions. The British have a long tradition of shaping Irish democracy in their interests and co-opting the political classes that emerge. They have displayed a remarkable capacity to channel Irish political trajectories in a particular direction, harness Irish leaderships to drive the strategy, and make the Irish believe it was their own idea. James Connolly wrote, ‘Ruling by fooling is a great British art. With great Irish fools to practice on.’

Thanks to the Good Friday Agreement, the future of the Northern state rests securely in a political and legal framework of terms and conditions comprehensively safeguarded within an intricate web of constitutional constraints that only Britain can interpret and adjudicate. No Irish citizen, elected or otherwise, can call an Irish unity poll in Ireland. That decision lies firmly in the hands of an English politician who doesn’t have a single vote in Ireland. That is Irish democracy British style.

A memorial to the hunger strikers recently unveiled in America implies that they died for the Good Friday Agreement. I find few concepts more disheartening than the implication that the ten IRA/INLA hunger strikers who died in the H-Blocks in 1981 paved the way for this internal settlement on British terms.

The Good Friday Agreement is a pacification project based on the principle that the model of Ireland as one nation is a discredited concept. It annuls the republican concept of national unity across the sectarian divide. It guarantees that unionists will remain British into perpetuity instead of sharing equal citizenship with the rest of their countrymen. A genuine republic recognizes and tolerates diversity but should never encourage and embrace conflicting national loyalties within its territory. The Good Friday Agreement attempts to ensure that unionists will remain forever in Ireland but not of it. It bakes in the British/Irish cleavage in national loyalties. It enshrines the sectarian dynamic. Thus, it guarantees that the political malignancy through which Britain historically manipulated and controlled Ireland will remain intact. No Irish Republican would have lifted a finger for that, much less have suffered a prolonged and agonising death for it.

Writing in his diary on the first day of his hunger strike, Bobby Sands noted, ‘what is lost here is lost for the Republic’. Later, he passed a comm to one of his comrades during a prison mass, which said, ‘Don’t worry, the Republic’s safe with me’. Unfortunately, the Republic would not prove safe in the hands of ambitious opportunists who would lay claim to Bobby’s legacy.

The British have awarded the Victoria Cross to a small number of soldiers who demonstrated remarkable bravery, or for some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or for extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. The American Congressional Medal of Honour has been awarded to a select few of their soldiers who displayed conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Many of these acts of undoubted courage were carried out impulsively in the heat of the moment, when the adrenalin was at its highest, and the intensity of close combat blurs the ability to rationalise and analyse one’s actions.

Think of the heroism involved in a hunger strike to death. What conspicuous bravery and pre-eminent acts of self-sacrifice were displayed by our Republican soldiers? How high above and beyond the call of duty did they reach in their determination to achieve their mission? And not in any act of impetuous audacity but in the grinding physical and mental attrition of slow starvation. An act of heroism conducted in an environment where one has up to two months and beyond to suffer an agonising death. Up to two months and beyond to contemplate and reflect upon the action undertaken and the consequences of that action upon oneself, one’s family, and the struggle. Up to two months and beyond as the body devours itself while prison officers leave delicious and nourishing food in one’s cell at every mealtime. It is a sacrifice where life is handed to you on a plate three times a day and must be shunned for what one believes is the greater good for your comrades and your country.

Between 1917 and 1981, 22 Irish Republicans died on hunger strikes protesting attempts by the enemies of the Irish Republic, both foreign and domestic, to criminalise the struggle for Irish freedom.

Today we honour the seven gallant IRA volunteers and their three INLA comrades who sacrificed all they had for their country between March and October of 1981. We also remember IRA volunteers Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, who died on hunger strikes in English prisons in 1974 and 1976, respectively.

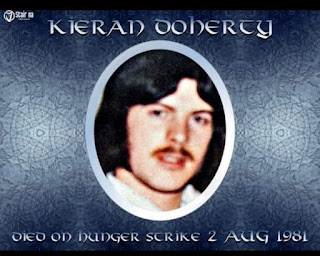

Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee, and Michael Devine. We salute you, and we never shall forget who you were and what you truly represented. Blessed are they who hunger for justice. Up the Republic!

⏩John Crawley is a former IRA volunteer and author of The Yank.

Forty-two years ago today, the hunger strikes in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh were still in progress. Ten Irish Republican prisoners had died of starvation, and ten more were refusing food. The last to die, INLA Volunteer Mickey Devine, passed away on August 20th. The hunger strikes would be called off on October 3rd. Many in the crowd today had not yet been born; for them, it is a historical event. Others of us were young men and women in 1981 and remember it as a contemporary event. To Republicans of all ages, that fateful period is seared into our souls as a defining moment in Irish history.

A sacrifice of such magnitude, suffering, and selfless devotion inspires admiration in even the most cynical of those motivated primarily by material self-interest. People who wouldn’t dream of skipping breakfast for any cause or principle couldn’t help but feel a measure of respect for the hunger strikers’ inspirational sacrifice. It also encouraged those of a more opportunistic mindset to see in the hunger strikes a moral well to draw from - an event to be relentlessly plundered to augment the electoral capital essential to advancing their private political ambitions.

The issue of political legitimacy has been at the core of much of what Irish political hunger strikes have been about, whether Irishmen and women have the fundamental right, as stated in the 1916 Proclamation, to organise and train her manhood to assert in arms the independence and sovereignty of Ireland, an Ireland defined by the Proclamation as the whole nation and all of its parts. Or whether this activity can be viewed by the enemies of Irish freedom as criminal acts.

Usually, when Irish Republican hunger strikers make demands, they are not presented in such stark ideological terms. But few who have been in prison can doubt that the sacrifices made and the hardships endured during protests were not about obtaining for others an easy life in jail but a real defence of our legitimate right to fight for the full freedom of our country without being treated as common criminals.

Great play is made of the narrative that the hunger strikes of 1981 paved the way for electoral politics for the Provisional movement back when it could still claim to be a Republican movement. Long before former comrades began advocating for a two-nations ‘New’ Ireland instead of the one-nation Republic we were assured they would lead us to. This narrative has become so embedded and unchallenged that it has evolved in some circles into the delusional claim that the hunger strikers died for the Good Friday Agreement.

Why does Britain continue to interfere in our internal affairs and strive to constitutionally enshrine and manipulate our differences and divisions? First and foremost is the strategic imperative of maintaining the political and territorial integrity of the United Kingdom. Modifying Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution from a territorial claim to a notional aspiration was a significant victory for the British. The Brits and the Unionists had continually protested that these articles were the real impediments to peace and stability, not partition. Articles 2 and 3 attempted to address the injustice of partition by declaring that Ireland is one nation. It had been treated as one nation by England for hundreds of years. Weakening Dublin’s claim to the six northeastern counties gives a veneer of democratic legitimacy to partition. It demonstrates that the Irish government has partnered with London in declining to acknowledge Ireland as one democratic unit and has conceded that fact in an international agreement. It is a credit to the negotiating skills of the British that diluting the Irish territorial claim to Ireland as a whole was the only binding constitutional change required by the Good Friday Agreement.

The British never forget that Ireland is their back door. England’s initial reason for invading Ireland was to enrich themselves through land and taxation and to prevent other European powers or contenders for the English throne from using Ireland as a base of operations. When British intelligence and security analysts cast their gaze across the Irish Sea, they observe an island of over thirty-two thousand square miles covering vital approaches to Britain’s national territory and seas. A land mass that permits rapid access to areas of the North Atlantic crucial to British defence interests, particularly the naval choke point between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom that Russian ships and submarines must navigate to reach the North Atlantic. An island whose territorial waters contain, or are in close proximity to, three-quarters of all underwater fibre-optic cables in the northern hemisphere. Cables that carry approximately ninety-seven percent of all global communications. Another consideration is that Britain’s strategic nuclear deterrent, consisting of Trident ballistic missiles on Vanguard-class submarines, is based at Faslane in Scotland. These subs have to pass through the narrow North Channel between Scotland and the North of Ireland when leaving or returning to base. Under no circumstances would a government independent of the United Kingdom be allowed unfettered control of that channel’s western flank if it can be avoided.

The Brits see in Ireland a bread basket and cattle ranch. An unsinkable aircraft carrier and potential ports for their warships and submarines. An island with approximately two million men and women of military age. An island where six of its counties are members of NATO, and the remaining twenty-six must somehow be manipulated or conned into joining.

The Brits see what they have always seen in Ireland. A geographical, material, and human resource to be exploited and one that must never be encouraged to become a united, sovereign, and independent Republic that could conceivably develop policies for the benefit of the Irish people that conflict with Britian’s strategic interests.

A crucial component of British strategy is reshaping the narrative on Irish unity. Wolfe Tone’s belief that unity between Planter and Gael would be achieved through breaking the connection with England and forging a joint civic identity is best replaced by, among other things, the concept of unity through commemorating joint service in the First World War when Irish Catholics and Protestants engaged in the mutual enterprise of killing Germans in Flanders. Some Nationalists believe that relationships with Unionists can be enhanced through attendance at British war commemorations and sentimentalising joint military service in the Imperial Army that executed the 1916 leadership - emphasising at all times that the only unity that matters lies in our cross-community debasement as levies and mercenaries for the foreign country that conquered us. As part of this campaign, British war memorials are springing up all over Ireland, and elements of the Irish Defence Forces play an increasing role as a ceremonial wing for the British army. Many of those pushing this agenda support entering NATO in the belief that Irish national security can best be preserved by joining in a military alliance with the country that endeavoured most to subdue us and continues to claim a substantial portion of our national territory.

Anyone who believes the British government will simply leave Ireland when the unionist population dwindles to an unsustainable level and close the door behind them is mistaken. The Brits play the long game and are working now, as they have been working for years, to shape the strategic environment and set the conditions for the constitutional future of a united Ireland that will work to their benefit. London can live with a united Ireland within the British Commonwealth and NATO. It will not tolerate a sovereign Republic immune to its influence. At the heart of the so-called Irish peace process lies the hidden agenda of a British war process.

Unionists did not partition Ireland - England did. It did so for deeper and far more strategic reasons than the refusal of a minority in six Irish counties to become subject to the democratic will of a national majority. England did not claim jurisdiction in Ireland for the benefit of unionists. England’s conquest of Ireland began centuries before the plantations. There was no Union and no Unionists when England’s sword first cut its genocidal swathe through Ireland. It doesn’t care about unionists beyond their utility as a bulwark against the evolution of a national civic identity. Ulster Unionists are pro-British for deep historical reasons that cannot be glibly dismissed, but they are not the British presence and must not be made so. The British presence is the presence of Britain’s jurisdictional claim to Ireland and the civil and military apparatus that gives that effect.

A relentless campaign is being waged to condition the Irish people to accept and legitimise a British constitutional component as an essential ingredient of a united Ireland. Unionists may be the excuse for this, but they are not the reason. The British will retain enormous influence in the internal affairs of this country if given a constitutional mandate to represent citizens from the Ulster Unionist tradition in the ludicrously named ‘New’ Ireland. The Brits will form alliances and build the political prestige of the leadership of any community who will help them pacify, normalise and stabilise the status quo. Britain may not always be able to rule Ireland directly, but with the help of an enduring civic division, it can help prevent us from harmoniously ruling ourselves.

When those who endorse the Good Friday Agreement speak of re-imaging a ‘New’ Ireland, what they really mean is refashioning the division between Planter and Gael and giving it a truly national dimension. When they speak of creating a United Ireland for everyone, they mean making all of Ireland British enough to encourage unionists to feel comfortable in it. Suggestions include discarding the national flag, changing the national anthem, and the South of Ireland re-joining the British Commonwealth. They talk of a New Ireland, an Agreed Ireland, a Shared Island. What they never speak of is the Irish Republic.

For a Republican, reaching out to unionists does not mean reaching out to them as foreigners who happen to live here but as our fellow citizens. Foreigners are born in another country. The vast majority of Ulster Unionists were born in Ireland. They must not be treated as the civil garrison of an alien state. That is not pluralism; that is submitting to the social and political modelling of colonial conquest. Robert Emmet did not request his epitaph be withheld until his country had taken its place as two nations among the nations of the earth.

Britain has no natural affinity with Orangeism beyond one of utility. The Brits had never demurred from negotiating over the heads of their allies in Ireland when it suited their interests. Tony Blair was quite happy to dismantle the Orange state if, by doing so, Westminster’s regional assembly at Stormont could achieve nationalist buy-in and become politically viable. Of course, Unionists didn’t like that. Many are motivated by an intense anti-Catholicism few Englishmen share. But the Provo trope of equating Unionist unease with impending nationalist victory is base sectarian reductionism.

Why is New Sinn Féin so heavily invested in Pax Britannica? Why have they internalised Britain’s definition of peace even though it was the British who injected the sectarian dynamic into Irish politics and are primarily responsible for political violence here? How have they been co-opted into a concept of Irish unity that converges with Britain’s analysis of the nature of the conflict and Britain’s strategy to resolve it?

There are many reasons for this Damascene conversion, but a key one is based on a similar principle that Free Staters followed after signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty - if you cannot do what counts, you make what you can do count. To do what counted to achieve the Irish Republic proved too dangerous and daunting for many Staters, so they decided to make the Treaty count, save their skins, open lucrative career paths, and shift the goalposts from the 32-county Sovereign Republic to a 26-county Dominion of the British Empire subordinate to the King. They then told their supporters that achieving managerial control of a state was what they had been fighting for all along and, thus, had won the war.

The Free State then proceeded to create a myth of ‘our’ Irish democracy defending itself against the ‘purists’ of Irish republicanism. The thing about democracy in Ireland is that the British have had centuries to mould it in their interests. They began, in part, by founding Maynooth Seminary in 1795. A major purpose, besides preventing the Irish Catholic clergy from being tainted by democratic and republican ideals acquired from a continental education, was to train the priests and bishops who would educate a rising Catholic middle class from whose ranks would emerge a loyal nationalist leadership amenable to reconciling Irish nationalist aspirations with British sovereignty.

The degree to which Britain succeeded in nurturing a loyal nationalist leadership can be seen in the Irish Parliamentary Party’s policy of harnessing Ireland to England’s war chariot in 1914 and John Redmond’s description of the 1916 rising as treason against the Irish people.

For republicans, democracy means popular control over public affairs by a free, informed, and equal citizenship without external impediment. For the British, democracy in Ireland is any mechanistic exhibition of electoral theatre that achieves a desired result despite the use or threat of force, bribery, censorship, partition, gerrymandering, or sectarian interventions. The British have a long tradition of shaping Irish democracy in their interests and co-opting the political classes that emerge. They have displayed a remarkable capacity to channel Irish political trajectories in a particular direction, harness Irish leaderships to drive the strategy, and make the Irish believe it was their own idea. James Connolly wrote, ‘Ruling by fooling is a great British art. With great Irish fools to practice on.’

Thanks to the Good Friday Agreement, the future of the Northern state rests securely in a political and legal framework of terms and conditions comprehensively safeguarded within an intricate web of constitutional constraints that only Britain can interpret and adjudicate. No Irish citizen, elected or otherwise, can call an Irish unity poll in Ireland. That decision lies firmly in the hands of an English politician who doesn’t have a single vote in Ireland. That is Irish democracy British style.

A memorial to the hunger strikers recently unveiled in America implies that they died for the Good Friday Agreement. I find few concepts more disheartening than the implication that the ten IRA/INLA hunger strikers who died in the H-Blocks in 1981 paved the way for this internal settlement on British terms.

The Good Friday Agreement is a pacification project based on the principle that the model of Ireland as one nation is a discredited concept. It annuls the republican concept of national unity across the sectarian divide. It guarantees that unionists will remain British into perpetuity instead of sharing equal citizenship with the rest of their countrymen. A genuine republic recognizes and tolerates diversity but should never encourage and embrace conflicting national loyalties within its territory. The Good Friday Agreement attempts to ensure that unionists will remain forever in Ireland but not of it. It bakes in the British/Irish cleavage in national loyalties. It enshrines the sectarian dynamic. Thus, it guarantees that the political malignancy through which Britain historically manipulated and controlled Ireland will remain intact. No Irish Republican would have lifted a finger for that, much less have suffered a prolonged and agonising death for it.

Writing in his diary on the first day of his hunger strike, Bobby Sands noted, ‘what is lost here is lost for the Republic’. Later, he passed a comm to one of his comrades during a prison mass, which said, ‘Don’t worry, the Republic’s safe with me’. Unfortunately, the Republic would not prove safe in the hands of ambitious opportunists who would lay claim to Bobby’s legacy.

The British have awarded the Victoria Cross to a small number of soldiers who demonstrated remarkable bravery, or for some daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or for extreme devotion to duty in the presence of the enemy. The American Congressional Medal of Honour has been awarded to a select few of their soldiers who displayed conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Many of these acts of undoubted courage were carried out impulsively in the heat of the moment, when the adrenalin was at its highest, and the intensity of close combat blurs the ability to rationalise and analyse one’s actions.

Think of the heroism involved in a hunger strike to death. What conspicuous bravery and pre-eminent acts of self-sacrifice were displayed by our Republican soldiers? How high above and beyond the call of duty did they reach in their determination to achieve their mission? And not in any act of impetuous audacity but in the grinding physical and mental attrition of slow starvation. An act of heroism conducted in an environment where one has up to two months and beyond to suffer an agonising death. Up to two months and beyond to contemplate and reflect upon the action undertaken and the consequences of that action upon oneself, one’s family, and the struggle. Up to two months and beyond as the body devours itself while prison officers leave delicious and nourishing food in one’s cell at every mealtime. It is a sacrifice where life is handed to you on a plate three times a day and must be shunned for what one believes is the greater good for your comrades and your country.

Between 1917 and 1981, 22 Irish Republicans died on hunger strikes protesting attempts by the enemies of the Irish Republic, both foreign and domestic, to criminalise the struggle for Irish freedom.

Today we honour the seven gallant IRA volunteers and their three INLA comrades who sacrificed all they had for their country between March and October of 1981. We also remember IRA volunteers Michael Gaughan and Frank Stagg, who died on hunger strikes in English prisons in 1974 and 1976, respectively.

Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee, and Michael Devine. We salute you, and we never shall forget who you were and what you truly represented. Blessed are they who hunger for justice. Up the Republic!

⏩John Crawley is a former IRA volunteer and author of The Yank.