The much vaunted Operation Kenova has seen the air let out of expectations over the Stakenife investigation. Are all inquiries into events in the North's violent conflict destined to get lost in the fog of British 'National Security'?

The investigation into the deaths of the most senior RUC officers shot dead during the North's violent conflict saw Drew Harris, former ACC PSNI in charge of legacy investigations and representative of M15, throw a log across the runaway train that was the Smithwick Tribunal.

This raises misgivings that the current much publicised historical investigation, Operation Kenova, has a sort of 'here we go again' inevitability ingrained into its function and ultimate purpose. The Jon Boutcher led inquiry has found no evidence to support Fulton's statements implicating Scappaticci in the Tom Oliver murder or in Fulton's own interrogation, which was another of Fulton's assertions at Smithwick.

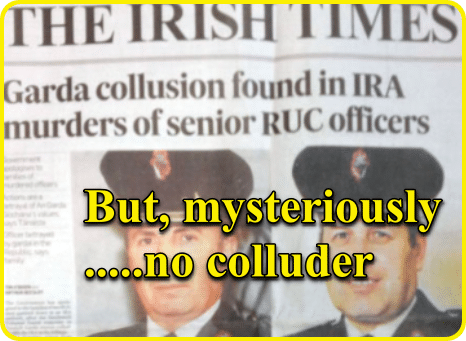

Deirdre Younge shows that the investigation into Breen and Buchanan came to a dead end. Is it realistic to expect a different outcome to flow from Kenova? Like Smithwick, like the PONI investigation into the Loughinisland murders, Kenova, already on the same track, seems to be heading for another case of collusion but no colluder.

This raises misgivings that the current much publicised historical investigation, Operation Kenova, has a sort of 'here we go again' inevitability ingrained into its function and ultimate purpose. The Jon Boutcher led inquiry has found no evidence to support Fulton's statements implicating Scappaticci in the Tom Oliver murder or in Fulton's own interrogation, which was another of Fulton's assertions at Smithwick.

Deirdre Younge shows that the investigation into Breen and Buchanan came to a dead end. Is it realistic to expect a different outcome to flow from Kenova? Like Smithwick, like the PONI investigation into the Loughinisland murders, Kenova, already on the same track, seems to be heading for another case of collusion but no colluder.

A new source tells Village that Smithwick Tribunal unduly relied on double agent Fulton’s evidence that Corrigan was the colluder. Confusingly, the PSNI named someone else as the colluder.

Concentrate Now: Smithwick Tribunal ended up with strange finding of ‘collusion’ but no name for the ‘colluder’ in murders of RUC men – apparently because Smithwick was swayed by the successor to the RUC (PSNI) giving untestable very late evidence privately naming someone more plausible than Owen Corrigan as the colluder. Smithwick always focused on Corrigan because the Cory Inquiry, which prompted the Smithwick Tribunal, unduly relied on 2003 evidence of dissembling double agent ‘Fulton’, now challenged by a Village source, that Corrigan gave relevant information to the IRA about the RUC men, though Fulton seems to have later changed his story (when giving evidence to Smithwick in 2011) to say that Corrigan gave information to the IRA only about informant Tom Oliver, and even the changed story was expressly and ignominiously disavowed by Smithwick in a recent High Court judgment to the extent it implied that Corrigan’s information led to Oliver’s death.

The Smithwick Tribunal was set up in 2005 and sat in public from 2011 until 2013, to examine the possibility of collusion in the deaths of Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Bob Buchanan, of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) who were murdered North of the Border in March 1989, after a brief meeting in Dundalk Garda Station. The purpose of their visit was to discuss a move against the IRA’s Tom ‘Slab’ Murphy, which had been ordered by then Northern Ireland Secretary of State, Tom King.

| Breen and Buchanan shot on the Edenappa Road about 500 yards from the border crossing |

In 1999 John Weir, a former RUC Sergeant who had been convicted of murder as part of a loyalist gang, drew up an affidavit for a defamation case which was published by the Barron Inquiry investigating the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, which asserted he personally knew that senior RUC Officers had colluded with the UVF. He alleged that Harry Breen supplied arms to the UVF in Portadown.

Smithwick implicitly accepted only that Breen was targeted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) because he was photographed in 1987 with weapons taken from Loughgall where eight IRA men were killed after British secret services got advanced warning of an ambush there.

The Tribunal spent years investigating alleged collusion of a different kind, between very different agents: by three gardaí in Dundalk Garda Station with the IRA. Confusingly, the PSNI arrived at the eleventh hour, with news of a ‘Fourth Man’, so defusing the allegations against the first three.

Though it found “no smoking gun” in Dundalk, the Tribunal weakly decided there was indeed less specific evidence of “collusion by gardaí” in the murders. Dutifully, Enda Kenny described these findings as “shocking”.

Smithwick implicitly accepted only that Breen was targeted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) because he was photographed in 1987 with weapons taken from Loughgall where eight IRA men were killed after British secret services got advanced warning of an ambush there.

The Tribunal spent years investigating alleged collusion of a different kind, between very different agents: by three gardaí in Dundalk Garda Station with the IRA. Confusingly, the PSNI arrived at the eleventh hour, with news of a ‘Fourth Man’, so defusing the allegations against the first three.

Though it found “no smoking gun” in Dundalk, the Tribunal weakly decided there was indeed less specific evidence of “collusion by gardaí” in the murders. Dutifully, Enda Kenny described these findings as “shocking”.

| Key figures in the Smithwick Tribunal |

The central figure in the Tribunal was retired Garda Detective Sergeant Owen Corrigan, who had served along the Border for his entire career. Corrigan was a pivotal figure in Special Branch in Dundalk until 1985.

Corrigan became the target of allegations ten years after the murders of Breen and Buchanan, in Bandit Country, a vivid account of the IRA in South Armagh, written by top British journalist Toby Harnden in 1999.

Corrigan was identified as ‘Garda X’ who was alleged to have furnished information to the IRA about Breen and Buchanan. Harnden was later to say that he had received information from an unidentified source in the RUC Special Branch claiming this. Kevin Myers, in the Irish Times, repeated these allegations unadulterated. Corrigan denies any wrongdoing and no finding of collusion with the IRA in relation to Breen and Buchanan was made against him despite the most thorough scrutiny by the Smithwick Tribunal.

| Toby Harnden: top journalist |

In its report on the Breen and Buchanan case in 2003, the Cory Collusion Inquiry details verbatim an interview with Harnden conducted in 2000. Cory damningly commented that:

The interviews revealed how little these gentlemen relied upon fact and how much they relied on suspicion and hypothesis.

Cory quotes Harnden as conceding:

A lot of what was told to him was circumstantial and that he did not believe he was in possession of evidence that could result in any charges.

Not surprisingly, Harnden did not give evidence to Smithwick.

Alan Mains, who had been Chief Superintendent Breen’s Sergeant in Armagh for three months before Breen’s death, had been assigned to help Harnden when he was writing his book. He changed his statement more than ten years after the murder to say Breen was fearful of going to Dundalk because he suspected Corrigan’s links to the IRA, though in fact it is clear that Breen was justifiably fearful on a number of grounds. Corrigan plausibly and consistently denies such links.

On recent visits north of the border, reliable loyalist and Unionist sources revealed to Village some details of Breen’s state of mind. They claim that, the night before he died, Breen met a close friend and revealed his fear of travelling to the border. He knew that an IRA action of some kind was being planned and, as a high-profile target, he feared for his life. The order to go to Dundalk, however, had come from the Chief Constable, Jack Hermon, based on the determination of then-Northern Secretary of State, Tom King, to tackle ‘Slab’ Murphy’s smuggling empire.

Alan Mains, who had been Chief Superintendent Breen’s Sergeant in Armagh for three months before Breen’s death, had been assigned to help Harnden when he was writing his book. He changed his statement more than ten years after the murder to say Breen was fearful of going to Dundalk because he suspected Corrigan’s links to the IRA, though in fact it is clear that Breen was justifiably fearful on a number of grounds. Corrigan plausibly and consistently denies such links.

On recent visits north of the border, reliable loyalist and Unionist sources revealed to Village some details of Breen’s state of mind. They claim that, the night before he died, Breen met a close friend and revealed his fear of travelling to the border. He knew that an IRA action of some kind was being planned and, as a high-profile target, he feared for his life. The order to go to Dundalk, however, had come from the Chief Constable, Jack Hermon, based on the determination of then-Northern Secretary of State, Tom King, to tackle ‘Slab’ Murphy’s smuggling empire.

| Owen Corrigan |

Apart altogether from the Breen and Buchanan murders, the Smithwick Tribunal heard an allegation made about the murder of a small farmer, Tom Oliver in July 1991. He was abducted from his home in Riverstown on the Cooley Peninsula by a group including double agent ‘Kevin Fulton’ aka Peter Keeley, a Newry man recruited from the British Army in 1979 to infiltrate the South Down IRA.

Kevin Fulton gave evidence over three days in December 2012 to the Smithwick Tribunal. In the course of his evidence Fulton said he was being paid a living allowance and accommodation by MI5 as part of its duty of care to him. He denied being involved in the kidnapping that led to Oliver’s death, and Smithwick accepted that.

Oliver was interrogated and murdered in Belleek in County Armagh. The allegation of murder was regarded as particularly important by Smithwick, being the one piece of direct evidence of collusion against a member of Dundalk station.

The problem is that under proper scrutiny allegations of collusion here – as absolutely elsewhere else – are contested and, in the end, unproven.

Fulton’s specific and momentous allegation was that in 1991 Corrigan met Patrick ‘Mooch’ Blair, a senior IRA member, in the car-park of Fintan’s Céilí House near Dundalk, and told Blair that Oliver was passing information about the IRA to the Garda Síochána. Blair is then alleged to have threatened to murder Tom Oliver, who was indeed killed soon afterwards. Fulton had become Blair’s driver. Fulton was a professionally trained dissembler and kept his handlers in MI5 and Army intelligence supplied with information for well over a decade.

Kevin Fulton gave evidence over three days in December 2012 to the Smithwick Tribunal. In the course of his evidence Fulton said he was being paid a living allowance and accommodation by MI5 as part of its duty of care to him. He denied being involved in the kidnapping that led to Oliver’s death, and Smithwick accepted that.

Oliver was interrogated and murdered in Belleek in County Armagh. The allegation of murder was regarded as particularly important by Smithwick, being the one piece of direct evidence of collusion against a member of Dundalk station.

The problem is that under proper scrutiny allegations of collusion here – as absolutely elsewhere else – are contested and, in the end, unproven.

Fulton’s specific and momentous allegation was that in 1991 Corrigan met Patrick ‘Mooch’ Blair, a senior IRA member, in the car-park of Fintan’s Céilí House near Dundalk, and told Blair that Oliver was passing information about the IRA to the Garda Síochána. Blair is then alleged to have threatened to murder Tom Oliver, who was indeed killed soon afterwards. Fulton had become Blair’s driver. Fulton was a professionally trained dissembler and kept his handlers in MI5 and Army intelligence supplied with information for well over a decade.

He sat only metres from me and I observed him throughout. He was a very impressive and credible witness and I have formed the view that his evidence was truthful.

Fulton now distances himself from Unsung Hero, a graphic book about his life. Nevertheless it is notable that at no stage in the book does Fulton mention a garda in Dundalk station passing information to the IRA. Nor is there any evidence that he passed information about Corrigan or other Dundalk gardaí, to his handlers.

Just weeks before his final report Cory came to Dundalk and met campaigners who were looking for an inquiry into the murders of Breen and Buchanan. When they asked if he was going to call for an inquiry he said: “I know something happened here but I have no evidence to call for an inquiry”. When asked “What do you need?” (He obviously needed direct evidence of collusion), normally reliable sources told Village: “They [the campaigners] wrote up a statement and gave it to Fulton to sign”. The statement said Owen Corrigan had passed information to Patrick ‘Mooch’ Blair in a car with Fulton.

Ultimately, for whatever reason, Cory was convinced after meeting Fulton and, according to sources, receiving a statement from Fulton. He cited Fulton’s evidence as a major reason for calling for a public inquiry into the Breen and Buchanan murders, focusing on Dundalk Garda station. That inquiry became the Smithwick Tribunal.

However, clearly there is a shadow over the statement which inspired Cory’s call for what became the Smithwick Tribunal. If this is so it rewrites the history of both inquiries.

Soon after that, Fulton went to Cory and read the statement. Village‘s sources, however, are adamant that the initial statement as given to Cory concerned Corrigan giving information to IRA member Patrick ‘Mooch’ Blair about the arrival of Breen and Buchanan at Dundalk Garda station. Village‘s sources insists that the statement described how Detective Sergeant Corrigan came out of Dundalk Station and said to ‘Mooch’ Blair – who was supposedly sitting in a car with Fulton – “they’re here”, after Breen and Buchanan had entered Dundalk.

Crucially, by the time Fulton reached Smithwick the alleged collusion had morphed into allegations about Corrigan’s passing ‘Mooch’ Blair information about Tom Oliver. Not having access to the original Cory documents it has not been possible to verify – and Patrick Blair and Corrigan utterly deny – the allegations. A description of this scandalous contradiction appeared in a 2007 story by Suzanne Breen in the Sunday Tribune.

Suzanne Breen did not name Fulton but reported:

An IRA informer also alleged Garda collusion in the Breen and Buchanan murders. A source told the Sunday Tribune that this informer claimed that he and ‘M’, a senior IRA figure, travelled to Dundalk on 20th March 1989. While Breen and Buchanan were inside the Garda station, a garda left the building and told the two IRA men that the two men would be leaving shortly.

Among the pieces of evidence accepted by Smithwick in a chapter devoted to Fulton’s evidence was firstly that Corrigan had been known as “our friend” to the IRA, someone who gave information to the South Armagh brigade. Fulton initially said he knew Corrigan was “our friend” but under cross-examination admitted he just “believed” he was. He alleged that on the day of the Breen and Buchanan murders a member of the local IRA unit told ‘Mooch’ Blair and Fulton that “our friend” gave information about Breen and Buchanan.

Among the pieces of evidence accepted by Smithwick in a chapter devoted to Fulton’s evidence was firstly that Corrigan had been known as “our friend” to the IRA, someone who gave information to the South Armagh brigade. Fulton initially said he knew Corrigan was “our friend” but under cross-examination admitted he just “believed” he was. He alleged that on the day of the Breen and Buchanan murders a member of the local IRA unit told ‘Mooch’ Blair and Fulton that “our friend” gave information about Breen and Buchanan.

| Patrick ‘Mooch’ Blair |

The first two pieces of Fulton’s evidence were hearsay, but the Oliver allegation was Smithwick’s only piece of direct evidence of collusion of any sort, by anybody, with the IRA after years of public and private hearings. It is this evidence, vehemently denied by Corrigan, which was the subject of the statement by the Tribunal that brought the Judicial Review to a halt and removes the taint of involvement from Corrigan.

But Smithwicks’ initial acceptance of Fulton’s evidence, about Corrigan and Oliver, ran directly contrary to evidence delivered to Smithwick from the PSNI and the UK Security Services, in May and October 2012. Smithwick stated, with apparent satisfaction, that the Tribunal was in a unique position as it was receiving evidence and co-operation from the Northern and UK authorities. However, he ignored or downplayed this evidence in his report. Anyone reading the report must work hard to find the details of this.

Everyone, including probably you dear reader, thinks the Smithwick Tribunal was about collusion, which everybody thinks it found, but ultimately not one allegation of collusion remained solid and firm at the conclusion of proceedings.

In a dramatic last-minute intervention, on 2 May 2012 PSNI Chief Inspector Roy McComb attested the following to the Tribunal:

The IRA had received information regarding Breen and Buchanan from a detective Garda officer who had not been publicly identified to the Smithwick Tribunal and that this individual had been paid a considerable amount of money for this information.

Intelligence indicated that this officer also provided information about Tom Oliver and continued to provide information to the IRA for a number of years.

This extraordinary information was underpinned by the then Assistant Chief Constable, now Deputy Head of the PSNI, Drew Harris, an officer significantly senior to McComb, who gave further evidence to the Tribunal, in October 2012. Harris stated:

I would make the point that the inquiry was provided with all the information which related to the murders of Breen and Buchanan. What has happened now is that more information has become available to the Police Service and, as I have said, that is live information and of the moment. The initial provision of information was both by ourselves and the Security Services, and… was a full disclosure of the information that we felt able to give.

Smithwick was being assailed by last-minute, game-changing new evidence.

Harris was cross-examined by Owen Corrigan’s Senior Council, Jim O’Callaghan SC:

Harris was cross-examined by Owen Corrigan’s Senior Council, Jim O’Callaghan SC:

Q “Were you aware, Mr Harris, when you read these five pieces of intelligence…that they were beneficial to my client, Mr Corrigan, who has been the focus of this Tribunal inquiry for a number of years”.

A “Yes”.

Q “Did you see any unfairness in the fact that the PSNI hadn’t released this information earlier?”.

A “This material, no, because this material was released as quickly as we could manage to release, given our other responsibilities”.

Counsel for the Tribunal Mary Laverty SC and Drew Harris had the following exchange (led by Laverty):

Q. “Do you believe Mr Harris that there is any information that you could obtain for the Tribunal in the near future” ?

A. “Well contact with an individual, and hopefully other individuals is ongoing and hopefully within a few days to a week I will know whether I have further information which will be of assistance”.

The cross-examination of Corrigan was overshadowed by the new information. When Roy McComb arrived with new intelligence, Owen Corrigan had been in the witness box for just one day; the cross- examination by the Tribunal hadn’t begun.

But while McComb and later Harris provided succour to the three gardaí who had been the relentless focus of the Tribunal, Senior Garda and their lawyers went on the offensive against the quality of this new intelligence. Diarmaid McGuinness SC fumed that he regarded the information as “nonsense on stilts”.

As it was impossible to “get behind” the intelligence, it was impossible to assess it. The concentration on methodology therefore distracted from the extraordinary content and the possibility it posed of identifying the ‘Fourth Man’.

In February 2013, counsel for the Tribunal Mary Laverty SC announced that the Tribunal had gone on to check out the new information with some PSNI and Garda Síochána members, but the inquiries had run into the ground.

The Tribunal unsurprisingly declared that the murder of Tom Oliver was not part of its remit, but then accepted evidence that Corrigan had given information that set him up for murder. This was an unusual approach and of course Corrigan took legal action by way of Judicial Review. Following discussions between the parties, on 25 May 2016, the Tribunal confirmed, in a statement read to the High Court, that, whatever evidence it had heard, its final report had made no finding that the killing of Oliver was as a result of information the ex-garda provided to the Provisional IRA.

The action was then struck out by the High Court on the following terms:

While the Tribunal accepted the evidence of Kevin Fulton there was no finding in the Tribunal’s report that the killing of Mr Oliver was as a result of the information provided by Mr Corrigan to the IRA.

The Smithwick Inquiry ended with an enigmatic conclusion: a collusion – which this article has shown was not satisfactorily proven, with no named colluder.

⏩ Deirdre Younge is a writer/producer/director.