While the general perception is that Unionism is a Right-wing set of beliefs, political commentator, Dr John Coulter explores the view - what if Unionism was to lurch to the Hard Left ideologically as a way forward into Northern Ireland’s next century?

To mention Unionism and socialism in the same breath seems like the ultimate political anathema, but we must always remember that Irish politics is very much the art of the impossible.

In 1981, if you told the newly-elected republican MP for Fermanagh South Tyrone, Owen Carron, that one day his party Sinn Fein would sit in a partitionist parliament at Stormont with the Rev Ian Paisley’s DUP as its power-sharing Executive partner, you probably would have been met with hysterical laughter. But it happened.

Likewise, in 1985, as that same Rev Paisley had stepped off the platform at Belfast City Hall after delivering his ‘Never, never, never, never’ speech at the massive Ulster Says No rally in the aftermath of the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement and you had told him that one day he would enter a power-sharing devolved government at Stormont with former Derry IRA commander Martin McGuinness as his deputy, you probably would have been met with the famous maxim: ‘Let me smell your breath!’. But it happened.

Similarly, after the most recent Dail General Election, if you had told the Leinster House establishment that rivals Fianna Fail and Fine Gael would form an historic coalition government to keep Sinn Fein out of power, you’d probably have been told ‘Aye right!’ But it happened.

In the face of demands for Unionism to become more liberal and progressive and present an avowedly moderate agenda compared to the 1970s Unionist Coalition Hard Right agenda, could an even more radical ideological partnership be conceived - hardline socialism with a defence of the Union?

At first sight, this may seem an impossibility given the past history of Unionism flirting with socialism. The old Northern Ireland Labour Party, which managed to clock up some minor gains against the original Unionist Party, which ran Stormont for more than half a century, is now defunct.

At one time, socialists within the ruling Unionist Party did have their own pressure group - Unionist Labour, but it had little influence against the Right-wing tide of pressure groups such as the Ulster Monday Club, the West Ulster Unionist Council, and even Ulster Vanguard before it became a political party.

Among the Unionist electorate, Left-leaning parties such as the Progressive Unionist Party and the Ulster Democratic Party have had little impact, although the PUP did win two seats in the original Northern Ireland Assembly mandate of 1998.

However, Unionism’s Christian fundamentalist wing dismissed the PUP as ‘the Shankill Soviet’, accusing the party’s hierarchy of openly flirting with Marxism and communism.

This was as a result of the uneasy relationship between working class loyalism and Protestant fundamentalism. The accusation from numerous loyalists was that Protestant evangelists would preach rabble-rousing sermons, resulting in young loyalists acting on them and ending up in jail, whereupon the evangelists would abandon such convicted loyalists as ‘sinners’.

Loyalism began to regard such preaching as a ‘Grand Old Duke of York’ strategy of leading Protestants up to the top of the hill politically - and then promptly abandoning them when a crisis hit.

This was most openly seen during the Troubles when the once DUP-supported Ulster Resistance Movement (of red berets fame!) in the Eighties was cut adrift politically by the party when various weapons scandals emerged.

When jailed loyalists began to question why they were being abandoned by the fundamentalists in Protestantism, the former began to look to other ideologies politically rather than similar theologies.

It was at this point in the conflict that socialism and especially the writings of Marx began to enter the working class loyalist mindset. And so the rift between mainstream Unionism and working class loyalism began under the misconception that it was impossible to be a Unionist and a hardline socialist at the same time, let alone be a Unionist and a Marxist.

This perception was also fuelled by the view that the IRA’s political wing, Sinn Fein, and the INLA’s political wing, the Irish Republican Socialist Party, were both Marxist to the core.

Put bluntly, too - many Marxists who would have sympathised with the class structure politics of the PUP also shared similar views to the Workers’ Party, which had emerged from the Official IRA.

At one time, a movement known as the British and Irish Communist Organisation (BICO) was quite prolific in putting our pamphlets and policy documents within the loyalist community. Some in loyalism even wanted to see a reformation of the old Communist Party of Northern Ireland.

So that’s the background, but what of Unionism in 2021 which finds itself in Northern Ireland’s centenary year as a minority ideology if the past three elections are taken into consideration.

Indeed, if Unionism as a political family cannot combat electorally the so-called ‘Alliance Bounce’ come next May’s expected Stormont General Election, Sinn Fein may well end up being the largest party in the Assembly, entitling it to the post of First Minister.

Whilst the terms ‘progressive liberal’ and ‘radical moderate’ are being kicked around Unionism as it tries to define itself in a post Brexit and post covid island, could the unthinkable become a workable reality - namely, Unionism becomes a Hard Left ideology in terms of social and economic issues, whilst remaining firm on the Union?

After all, the DUP under Paisleyism was seen to be on the Right in terms of the Union, but on the Left in terms of everyday ‘bread and butter constituency issues’.

Unionism may also be hesitant to take a leap to the Hard Left given the demise of Jeremy Corbyn in the British Labour Party and the fact in Dublin’s Leinster House, a major contributing factor in Fianna Fail and Fine Gael forming their historic pact to keep out the ‘Shinners’ was because Sinn Fein’s Marxist economic agenda was ‘pie in the sky’ politics.

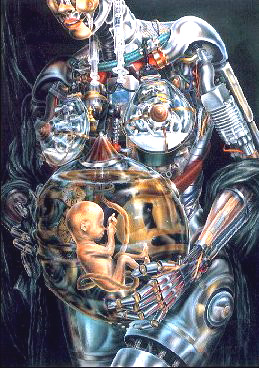

However, a viewpoint exists theologically - albeit a minority view - that Jesus Christ was really the first communist when the New Testament Sermon on the Mount is taken into consideration.

It has also been suggested that Karl Marx based communism on Christ’s Beatitudes by simply removing God from the political equation.

As Northern Ireland becomes more secular and pluralist in its society, could Unionism offer a ‘Shared Union’ to the island of Ireland which could adopt a Hard Left interpretation of The Beatitudes, thus keeping the Christian Churches on board electorally.

Summarising The Beatitudes in modern English, they are about Putting People First - putting pupils first, putting patients first, and putting pensioners first.

A ‘Shared Union’ would also emphasise that conditions such as the pandemic, cancer and autism does not recognise borders, or Orange and Green politics.

The bottom line for Unionism is, that in moving forward as an ideology, it may have to consider ideas which previously were perceived as electorally impossible.

In this case, perhaps Unionism as a body politic should move beyond so-called ‘progressive liberalism’ to a position where on everyday issues which affect people’s lives, it adopts a Hard Left approach.

In this scenario, could Unionism pinch a political trick or two from the so-called ‘liberation theology’ which the Catholic Church used as a basis against totalitarian regimes in South America?

To mention Unionism and socialism in the same breath seems like the ultimate political anathema, but we must always remember that Irish politics is very much the art of the impossible.

In 1981, if you told the newly-elected republican MP for Fermanagh South Tyrone, Owen Carron, that one day his party Sinn Fein would sit in a partitionist parliament at Stormont with the Rev Ian Paisley’s DUP as its power-sharing Executive partner, you probably would have been met with hysterical laughter. But it happened.

Likewise, in 1985, as that same Rev Paisley had stepped off the platform at Belfast City Hall after delivering his ‘Never, never, never, never’ speech at the massive Ulster Says No rally in the aftermath of the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement and you had told him that one day he would enter a power-sharing devolved government at Stormont with former Derry IRA commander Martin McGuinness as his deputy, you probably would have been met with the famous maxim: ‘Let me smell your breath!’. But it happened.

Similarly, after the most recent Dail General Election, if you had told the Leinster House establishment that rivals Fianna Fail and Fine Gael would form an historic coalition government to keep Sinn Fein out of power, you’d probably have been told ‘Aye right!’ But it happened.

In the face of demands for Unionism to become more liberal and progressive and present an avowedly moderate agenda compared to the 1970s Unionist Coalition Hard Right agenda, could an even more radical ideological partnership be conceived - hardline socialism with a defence of the Union?

At first sight, this may seem an impossibility given the past history of Unionism flirting with socialism. The old Northern Ireland Labour Party, which managed to clock up some minor gains against the original Unionist Party, which ran Stormont for more than half a century, is now defunct.

At one time, socialists within the ruling Unionist Party did have their own pressure group - Unionist Labour, but it had little influence against the Right-wing tide of pressure groups such as the Ulster Monday Club, the West Ulster Unionist Council, and even Ulster Vanguard before it became a political party.

Among the Unionist electorate, Left-leaning parties such as the Progressive Unionist Party and the Ulster Democratic Party have had little impact, although the PUP did win two seats in the original Northern Ireland Assembly mandate of 1998.

However, Unionism’s Christian fundamentalist wing dismissed the PUP as ‘the Shankill Soviet’, accusing the party’s hierarchy of openly flirting with Marxism and communism.

This was as a result of the uneasy relationship between working class loyalism and Protestant fundamentalism. The accusation from numerous loyalists was that Protestant evangelists would preach rabble-rousing sermons, resulting in young loyalists acting on them and ending up in jail, whereupon the evangelists would abandon such convicted loyalists as ‘sinners’.

Loyalism began to regard such preaching as a ‘Grand Old Duke of York’ strategy of leading Protestants up to the top of the hill politically - and then promptly abandoning them when a crisis hit.

This was most openly seen during the Troubles when the once DUP-supported Ulster Resistance Movement (of red berets fame!) in the Eighties was cut adrift politically by the party when various weapons scandals emerged.

When jailed loyalists began to question why they were being abandoned by the fundamentalists in Protestantism, the former began to look to other ideologies politically rather than similar theologies.

It was at this point in the conflict that socialism and especially the writings of Marx began to enter the working class loyalist mindset. And so the rift between mainstream Unionism and working class loyalism began under the misconception that it was impossible to be a Unionist and a hardline socialist at the same time, let alone be a Unionist and a Marxist.

This perception was also fuelled by the view that the IRA’s political wing, Sinn Fein, and the INLA’s political wing, the Irish Republican Socialist Party, were both Marxist to the core.

Put bluntly, too - many Marxists who would have sympathised with the class structure politics of the PUP also shared similar views to the Workers’ Party, which had emerged from the Official IRA.

At one time, a movement known as the British and Irish Communist Organisation (BICO) was quite prolific in putting our pamphlets and policy documents within the loyalist community. Some in loyalism even wanted to see a reformation of the old Communist Party of Northern Ireland.

So that’s the background, but what of Unionism in 2021 which finds itself in Northern Ireland’s centenary year as a minority ideology if the past three elections are taken into consideration.

Indeed, if Unionism as a political family cannot combat electorally the so-called ‘Alliance Bounce’ come next May’s expected Stormont General Election, Sinn Fein may well end up being the largest party in the Assembly, entitling it to the post of First Minister.

Whilst the terms ‘progressive liberal’ and ‘radical moderate’ are being kicked around Unionism as it tries to define itself in a post Brexit and post covid island, could the unthinkable become a workable reality - namely, Unionism becomes a Hard Left ideology in terms of social and economic issues, whilst remaining firm on the Union?

After all, the DUP under Paisleyism was seen to be on the Right in terms of the Union, but on the Left in terms of everyday ‘bread and butter constituency issues’.

Unionism may also be hesitant to take a leap to the Hard Left given the demise of Jeremy Corbyn in the British Labour Party and the fact in Dublin’s Leinster House, a major contributing factor in Fianna Fail and Fine Gael forming their historic pact to keep out the ‘Shinners’ was because Sinn Fein’s Marxist economic agenda was ‘pie in the sky’ politics.

However, a viewpoint exists theologically - albeit a minority view - that Jesus Christ was really the first communist when the New Testament Sermon on the Mount is taken into consideration.

It has also been suggested that Karl Marx based communism on Christ’s Beatitudes by simply removing God from the political equation.

As Northern Ireland becomes more secular and pluralist in its society, could Unionism offer a ‘Shared Union’ to the island of Ireland which could adopt a Hard Left interpretation of The Beatitudes, thus keeping the Christian Churches on board electorally.

Summarising The Beatitudes in modern English, they are about Putting People First - putting pupils first, putting patients first, and putting pensioners first.

A ‘Shared Union’ would also emphasise that conditions such as the pandemic, cancer and autism does not recognise borders, or Orange and Green politics.

The bottom line for Unionism is, that in moving forward as an ideology, it may have to consider ideas which previously were perceived as electorally impossible.

In this case, perhaps Unionism as a body politic should move beyond so-called ‘progressive liberalism’ to a position where on everyday issues which affect people’s lives, it adopts a Hard Left approach.

In this scenario, could Unionism pinch a political trick or two from the so-called ‘liberation theology’ which the Catholic Church used as a basis against totalitarian regimes in South America?

|

Follow Dr John Coulter on Twitter @JohnAHCoulter Listen to commentator Dr John Coulter’s programme, Call In Coulter, every Saturday morning around 10.15 am on Belfast’s Christian radio station, Sunshine 1049 FM. Listen online. |