People And Nature ☭ A vigil was held in Manchester’s Chinatown on Friday, to remember the victims of the fire in a block of flats in the Xinjiang province of China, Bob Myers writes.

A friend of ours, who is active in the Hong Kong solidarity movement, had let us know about the vigil. I went there with a friend.

About 30 young Chinese gathered – all overseas students I would say, not Manchester resident Chinese.

It was very moving, as the demonstrators were clearly very worried about protesting in public and wary of us – the only non Chinese there – and of each other. (Manchester has a big Chinese embassy and lots of security agents.)

Clearly most of the people didn’t know each other and didn’t talk to each other. (There are tens of thousands of Chinese students in Manchester). But one guy put down the posters you can see in the photos.

So it was more than just a memorial vigil. There was a list of four demands:

1 Allow public mourning

2 End brutal lockdown

3. Release arrested people

4. Defend people’s constitutional rights.

Another poster says: “Give me liberty or give me death.”

No-one said anything, people just stood there looking at the candles. Many passing Chinese people stopped to take photos.

My friend talked with one young woman, and she said: “We don’t know how to organise a protest. You know how to do it but we don’t.”

After we left we spotted the posters in the final picture, with the poem, stuck on a wall. Urumqi Road is where the fire took place. 5 December 2022.

Some links about China

➤The Chuang blog

➤ China Labour Bulletin

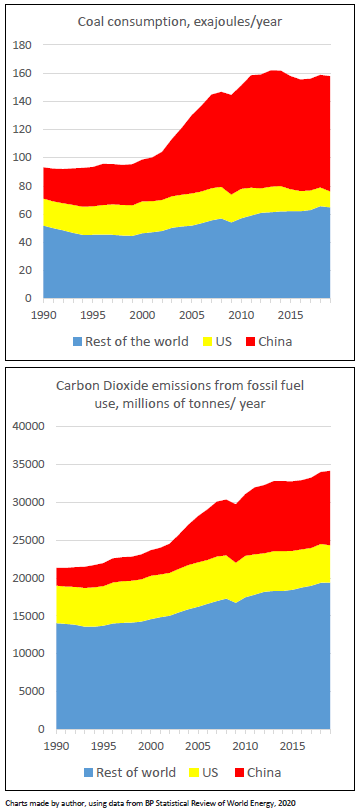

➤Xi Jinping’s coal stokes the climate fire – from People & Nature, January 2021

About 30 young Chinese gathered – all overseas students I would say, not Manchester resident Chinese.

It was very moving, as the demonstrators were clearly very worried about protesting in public and wary of us – the only non Chinese there – and of each other. (Manchester has a big Chinese embassy and lots of security agents.)

Clearly most of the people didn’t know each other and didn’t talk to each other. (There are tens of thousands of Chinese students in Manchester). But one guy put down the posters you can see in the photos.

So it was more than just a memorial vigil. There was a list of four demands:

1 Allow public mourning

2 End brutal lockdown

3. Release arrested people

4. Defend people’s constitutional rights.

Another poster says: “Give me liberty or give me death.”

No-one said anything, people just stood there looking at the candles. Many passing Chinese people stopped to take photos.

My friend talked with one young woman, and she said: “We don’t know how to organise a protest. You know how to do it but we don’t.”

After we left we spotted the posters in the final picture, with the poem, stuck on a wall. Urumqi Road is where the fire took place. 5 December 2022.

Some links about China

➤The Chuang blog

➤ China Labour Bulletin

➤Xi Jinping’s coal stokes the climate fire – from People & Nature, January 2021