One of the main differences between closed prisons and Cat-Ds (open nicks) is the opportunity for at least some prisoners to experience Release on Temporary Licence (ROTL). I’ve had a few questions from readers about ROTL, so I thought that this would be a good subject for a blog post.

Not all prisoners who make it to open conditions will get ROTL, which – as we are constantly reminded – is a privilege, not an entitlement. The idea behind temporary release is to allow prisoners who have been inside for a lengthy stretch the chance to start the slow process of acclimatising themselves to the outside world again, as well as giving inmates who have made the journey through the various security categories of closed prisons to a Cat-D the chance to demonstrate that they can behave like normal, law-abiding citizens.

Broadly speaking ROTL comes in two main varieties: Resettlement Day Release (RDR) and Resettlement Overnight Release (ROR). I’ve written a little about ROR (‘home leave’) in my recent posts on coming home for temporary leave at Christmas. However, I haven’t yet shared my own experiences of RDR or ‘townies’, as many cons call them.

When I was eventually granted my Cat-D status – after quite a long process of applications and appeals – I still had to wait for around six weeks before I was offered a place at the nearest open nick. That was actually pretty good going as I’ve know lads wait many months for a transfer since Cat-D jails are short of available spaces.

Shortly after my arrival at the new prison I was granted Special Purpose Leave (SPL) to go into the local town, along with a couple of fellow cons and a senior officer. Three were lifers, while the other lad and I were fixed-termers. To be honest, we were pretty much left to our own devices for a couple of hours.

Going into town in a normal vehicle was a very strange experience, even after having only been in jail for less than two years. I had become accustomed to travelling between nicks in a ‘sweatbox’ (prison van), locked into a tiny cubicle, handcuffed and dressed in prison clothing. My only glimpses of the outside world had been from the small tinted window of the van. Now I was sitting in a people carrier being driven into the local town by an officer in civvy clothing and behaving like a ‘normal’ person again.

We walked around the town – which was one I’d never visited previously – and had a coffee. I think that it was getting used to crowds in shops and dealing with the busy traffic that I found most difficult. Imagine if it had that effect on me after my relatively short period of incarceration, what it must be like for a lifer who has been in a closed prison for 20 years or more?

At one point we all split up and arranged to meet near the town war memorial. As I walked up the road, I reflected that this was my first moment of actual freedom: no screws, no other cons, no locked gates… just an anonymous member of the public strolling through a small market town. Other than my prison ID card in my pocket, there was nothing that would have given the game away – that I was actually still a serving prisoner who would be back in prison within a couple of hours.

Was I tempted to do a runner? Well, I think that every con, at some stage, must fantastise about seeing an open gate. Human beings are not made to be locked up in small boxes and many prisoners do think about escape. However, if such a stupid idea did cross my mind momentarily while I was out in town on my own, that was where it very definitely stayed.

The consequences of absconding, either from the prison (which had no fences) or while on ROTL would have been devastating: the certainty of an immediate manhunt by police, accompanied by media coverage and then recapture, transfer to a Cat-B prison on ‘escapee’ status (wearing a green and yellow patch clown suit for months – or even the rest of my sentence) and no chance of ever getting a lower security category again.

To be honest, I was still a little nervous as I waited at the meeting point. What if the others failed to turn up? Fortunately, nothing went awry and after some more tourism and a bit of shopping we went back to the nick. All very painless, really. Of course, the fact that I’d had a successful accompanied ROTL in town stood me in very good stead for the rest of my prison stretch.

Following that first day out, I had to wait about another three months before I finally got my first unaccompanied day release. I’d applied almost as soon as I arrived in the Cat-D jail, but the processing of my application was delayed because my offender supervisor (inside probation) was on extended leave. This particular open nick has serious problems with staffing its Offender Management Unit (OMU), so there was no cover available to deal with his caseload while he was off work.

Eventually, however, my application was processed and I received the memorandum from OMU calling me to attend a ROTL Board. This is a bit like an inquisition during which a governor grade and your offender supervisor cross-examine you about why you have applied for temporary leave. They also ask questions about how you would cope with certain stressful situations while out of the prison. A few days later I had a note via the internal post – a ROTL 5 form – informing me that my application had been successful and I had been approved for my first townie.

Going out on my own for the day was a very interesting experience. I picked up my paper licence from the OMU and signed out at the gatehouse. The prison laid on a unmarked minibus to ferry us into town – about a 20 minute trip – and dropped us off in a car park. We were then free to spend the rest of the day as we wanted. I visited the local library, did some shopping (back then we were still allowed to buy certain items while on ROTL, such as clothing, books, DVDs and CDs as long as we had a signed reception application with us).

As it was summer, a couple of us bought some lunch and sat in the sun in the local park. It was an amazing experience to have choices again: what to eat from lunch, what to buy in a shop. Of course, we had to ensure that we behaved like law-abiding citizens, although that wasn’t a problem for any of us.

To be honest, although ‘townies’ were welcome breaks from the dreary routine of prison life, they weren’t essential for me personally. I’d not been away for all that long (some of my fellow cons had been in jail for 20 or even 30 years), so even if my application had been rejected, it wouldn’t have altered the fact that as a fixed-termer, I’d be going home eventually. However, for the lifers these day trips were absolutely essential.

As I’ve mentioned in other posts about open prisons, about half of those who make it to Cat-D will be serving indeterminate sentences – either life or an Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (IPP). In both cases, their eventual release will depend entirely on a recommendation by the Parole Board which will be looking for evidence of manageable risk if the prisoner is released back into the community on licence.

A major element of risk assessment is the readiness of the individual to abide by his or her licence conditions and to steer clear of committing any further offences. It also includes an analysis of potentially risky behaviours – including use of drugs and alcohol – or behaving in a way that might give rise to recall to prison. Making such judgement calls can be highly subjective and it can be very difficult for Parole Board members to reach fair decisions unless there is some evidence to consider.

In a closed prison inmates’ behaviour is closely controlled. They often spend a considerable proportion of their day locked behind a heavy steel door. However, as anyone with experience of the prison system will know all too well, good behaviour in custody does not necessarily mean that a prisoner will behave well when freed from these constraints. So before important decisions about granting parole can be made, there needs to be a degree of risk-taking by the prison authorities and that is where Cat-D nicks are important.

In recent years, the process of allowing prisoners in open prisons to access ROTL has been tightened up. What often used to be an almost automatic rubber-stamping of applications has now become a complex process that can involve regular psychological assessments and constant risk management, particularly when it concerns prisoners who are considered to present a high risk of harm should they reoffend. Following a small number of very high profile ‘ROTL failures’ in 2012 and 2013, the government intervened and in August introduced temporary new rules for granting ROTL.

Now, it is also important to put the issue of these ROTL failures into context. According to data compiled by the Prison Governors’Association (PGA), ROTL was granted on 485,000 separate occasions during 2012. Incidents involving further offences being committed amount to no more than five in every 100,000 ROTLs (or 0.005%). In pretty much any other public service a successful level of delivery like that would be trumpeted from the rooftops by the politicians responsible. Sadly, not when it comes to our prisons.

In fact, many ROTL failures are more to do with arriving back late. This can be caused by transport delays, traffic problems or other mundane hitches, rather than actual absconding or because a prisoner on leave has committed new offences.

Whenever there has been some incident of a con absconding on a temporary licence or committing some new offence the tabloid media seems to have a feeding frenzy demanding that ROTL be stopped or cut back. In fact, the new ROTL guidance issued by the Ministry of Justice effectively prohibits temporary release – or even Cat-D status – for any prisoner who has previously attempted to escape or abscond, or even arrived back late at the gate when on ROTL – for which he or she will already have been punished at an adjudication.

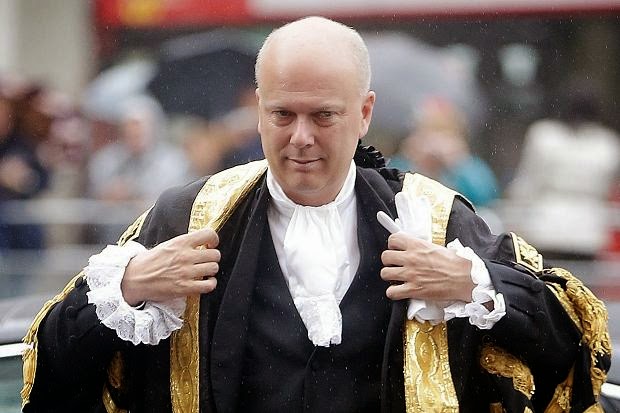

This presents a serious potential barrier to release for any lifer or IPP who is barred from being granted ROTL. It also makes the work of the Parole Board much harder since it reduces the evidence that they will have to consider when it comes to manageable risk. In practice it is likely to mean that lifers and IPPs will spend many more years inside than they would have prior to the latest ideologically-motivated meddling by Chris Grayling and his desk-jockeys at Petty France... and all at the taxpayers’ expense, as usual.

I foresee that we will have all manner of costly legal challenges to the new ROTL policy, as we have with all sorts of previous knee-jerk reactions in our criminal justice system. However – as with all the other disasters and rebuffs Team Grayling have experienced in the Court of Appeal and the High Court in recent months – I doubt if Calamity Chris will allow the question of lawfulness, or indeed the rule of law, to get in the way of a quick headline in the Daily Mail.

|

| Cat-D: no more locked gates |

Broadly speaking ROTL comes in two main varieties: Resettlement Day Release (RDR) and Resettlement Overnight Release (ROR). I’ve written a little about ROR (‘home leave’) in my recent posts on coming home for temporary leave at Christmas. However, I haven’t yet shared my own experiences of RDR or ‘townies’, as many cons call them.

When I was eventually granted my Cat-D status – after quite a long process of applications and appeals – I still had to wait for around six weeks before I was offered a place at the nearest open nick. That was actually pretty good going as I’ve know lads wait many months for a transfer since Cat-D jails are short of available spaces.

Shortly after my arrival at the new prison I was granted Special Purpose Leave (SPL) to go into the local town, along with a couple of fellow cons and a senior officer. Three were lifers, while the other lad and I were fixed-termers. To be honest, we were pretty much left to our own devices for a couple of hours.

|

| No more handcuffs |

We walked around the town – which was one I’d never visited previously – and had a coffee. I think that it was getting used to crowds in shops and dealing with the busy traffic that I found most difficult. Imagine if it had that effect on me after my relatively short period of incarceration, what it must be like for a lifer who has been in a closed prison for 20 years or more?

|

| The magic 'ROTL 7' licence to go on temporary leave |

Was I tempted to do a runner? Well, I think that every con, at some stage, must fantastise about seeing an open gate. Human beings are not made to be locked up in small boxes and many prisoners do think about escape. However, if such a stupid idea did cross my mind momentarily while I was out in town on my own, that was where it very definitely stayed.

|

| HMP Kirkham: open gate at Cat-D |

To be honest, I was still a little nervous as I waited at the meeting point. What if the others failed to turn up? Fortunately, nothing went awry and after some more tourism and a bit of shopping we went back to the nick. All very painless, really. Of course, the fact that I’d had a successful accompanied ROTL in town stood me in very good stead for the rest of my prison stretch.

Following that first day out, I had to wait about another three months before I finally got my first unaccompanied day release. I’d applied almost as soon as I arrived in the Cat-D jail, but the processing of my application was delayed because my offender supervisor (inside probation) was on extended leave. This particular open nick has serious problems with staffing its Offender Management Unit (OMU), so there was no cover available to deal with his caseload while he was off work.

Eventually, however, my application was processed and I received the memorandum from OMU calling me to attend a ROTL Board. This is a bit like an inquisition during which a governor grade and your offender supervisor cross-examine you about why you have applied for temporary leave. They also ask questions about how you would cope with certain stressful situations while out of the prison. A few days later I had a note via the internal post – a ROTL 5 form – informing me that my application had been successful and I had been approved for my first townie.

|

| Notification of a ROTL Board from OMU |

|

| Sandwiches in the park |

To be honest, although ‘townies’ were welcome breaks from the dreary routine of prison life, they weren’t essential for me personally. I’d not been away for all that long (some of my fellow cons had been in jail for 20 or even 30 years), so even if my application had been rejected, it wouldn’t have altered the fact that as a fixed-termer, I’d be going home eventually. However, for the lifers these day trips were absolutely essential.

As I’ve mentioned in other posts about open prisons, about half of those who make it to Cat-D will be serving indeterminate sentences – either life or an Indeterminate Sentence for Public Protection (IPP). In both cases, their eventual release will depend entirely on a recommendation by the Parole Board which will be looking for evidence of manageable risk if the prisoner is released back into the community on licence.

|

| Standard ROTL licence conditions |

In a closed prison inmates’ behaviour is closely controlled. They often spend a considerable proportion of their day locked behind a heavy steel door. However, as anyone with experience of the prison system will know all too well, good behaviour in custody does not necessarily mean that a prisoner will behave well when freed from these constraints. So before important decisions about granting parole can be made, there needs to be a degree of risk-taking by the prison authorities and that is where Cat-D nicks are important.

In recent years, the process of allowing prisoners in open prisons to access ROTL has been tightened up. What often used to be an almost automatic rubber-stamping of applications has now become a complex process that can involve regular psychological assessments and constant risk management, particularly when it concerns prisoners who are considered to present a high risk of harm should they reoffend. Following a small number of very high profile ‘ROTL failures’ in 2012 and 2013, the government intervened and in August introduced temporary new rules for granting ROTL.

|

| Consequences of ROTL failure |

In fact, many ROTL failures are more to do with arriving back late. This can be caused by transport delays, traffic problems or other mundane hitches, rather than actual absconding or because a prisoner on leave has committed new offences.

Whenever there has been some incident of a con absconding on a temporary licence or committing some new offence the tabloid media seems to have a feeding frenzy demanding that ROTL be stopped or cut back. In fact, the new ROTL guidance issued by the Ministry of Justice effectively prohibits temporary release – or even Cat-D status – for any prisoner who has previously attempted to escape or abscond, or even arrived back late at the gate when on ROTL – for which he or she will already have been punished at an adjudication.

|

| Trying to make a silk purse... |

I foresee that we will have all manner of costly legal challenges to the new ROTL policy, as we have with all sorts of previous knee-jerk reactions in our criminal justice system. However – as with all the other disasters and rebuffs Team Grayling have experienced in the Court of Appeal and the High Court in recent months – I doubt if Calamity Chris will allow the question of lawfulness, or indeed the rule of law, to get in the way of a quick headline in the Daily Mail.

And you were allowed a sandwich rather than bread and water. English society must have been on the verge of collapse that day.

ReplyDeleteHAVEN - Books to Prisoners

ReplyDelete